Getting back into teaching the details of chemistry to my 12th grade students has been a trip. I had completely forgotten how weird the subject of chemistry is, since it has this long, deeply bewildering, bizarre historical arc, but is taught in "reverse time," pretty much, with quantum physics, electron orbitals, electron quantum numbers, the Aufbau rule, Hund's rule, the Pauli Exclusion Principle and all of that taught up front. Students want to know simple things, like, why ammonium nitrate is made of three different gases but is itself a weird solid at room temperature? Why do some things explode when you throw them in water? Why is matter the way it is, basically? And chemistry starts answering by telling this incredibly outlandish story about tiny particles at unimaginably small spatial scales, and incomprehensibly large quantities like moles, and even weirder, electrons, which have almost no mass but have a charge equal to but opposite from protons, etc.

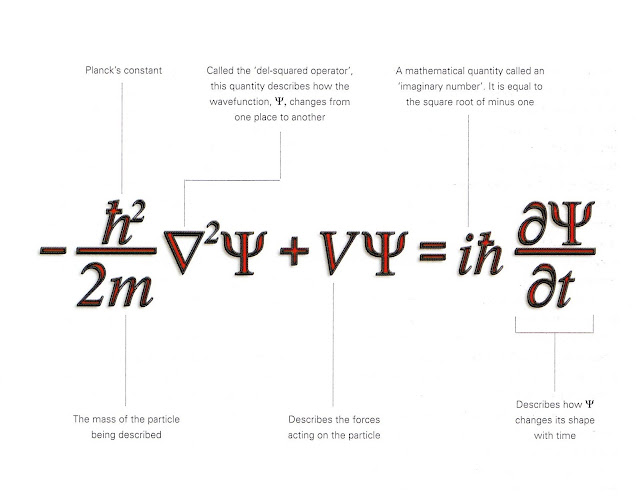

My sister once caused a ton of dinner table scoffing, when she was about 15 years old, and ventured that she "didn't believe in atoms," because she couldn't see them. "Even scientists don't agree on what they are." My oldest brother, in particular, found it a hilarious attitude. But really, aren't we just sort of assenting to a bunch of inherited 20th Century research by a handful of brilliant physicists whose mathematics, methods, and conclusions are way, way over the head even of most chemistry teachers? I mean, at my Ivory Tower undergrad, in my junior year lab, the teacher helped us derive Schrödinger's wave equation, but I'll be damned if I truly understood it at that time, let alone now, where I take one look at its simplified form and just shrug.

Trust me, I'm a physicist

The sad fact is we landed in a zone where we basically have to tell our students to accept a ton of assertions on faith, the exact opposite of what their science minds ought to be doing. It's ultimately okay, probably. But it creates a weird tension for the more inquisitive students, who really want to know why. Why are orbitals shaped the way they are? Why do they only contain a maximum of a certain number of electrons? Why is matter lazy and electrons fill the lowest energy level shells first? What does it mean that electrons are both waves and particles? And what the hell does any of this have to do with chemistry?

Those are all great questions.

Science topics taught in K-12 are pretty much just delivering a body of pre-existing knowledge. This makes it very difficult for students to *do science*, as an activity, because most of the students very quickly perceive the sad truth: *it has already BEEN DONE*. Most of the labs are just drearily working through dumbed down versions of experiments that have already been done a billion times. To teach the great, exhilarating experience of *actually discovering something* is quite challenging. If one wanted to teach "discovery science," it would take a very, very long time. And for the students who are more oriented toward applied science, and who don't mind accepting the gigantic mountain of existing knowledge at face value, discovery based activities are tedious in the extreme. In fact, some try their best to engage, but then, when they learn at the end that, of course, whatever they "discovered" has been known since 1789 or whatever, they get pissed. Can you blame them?

I've been leaning toward cultivating experiences where, at least, each individual student has their own personal "aha!" moments, even if the original "aha!" was hundreds of years ago. I've also been trying to incorporate as much of the surprising or weird as possible, which many students find entertaining. Here's a video of what happens when you throw a kg of sodium into water, for example:

No comments:

Post a Comment

This is an anonymous blog, mostly in an effort to respect the 12th tradition of Alcoholics Anonymous. Any identifying information in comments will result in the comment not being approved.